Volume One

Ancient and Medieval States

Background

Medieval China

Cash: Chinese Cast Coinage

|  |

State of Yan (300-222 BC) Ae Round coin. Obverse: Ming Hua. Reverse: plain. 25mm 2.6gm. Hartill 6.21 | |

Coins proper begin in Lydia in the seventh century BC, and in China shortly afterwards. In both areas, however, and probably more generally, true coins were preceded by token coinages: metal rings and axes in Europe and a great variety of objects in China: tortoise shells, cowry shells, gold foil, spade pieces and knives. Spade pieces come in many thousands of types, grouped by scholars and collectors by shapes and inscriptions and ascribed by find locations to the many changing kingdoms that were to consolidate into the first Qin Empire (250 BC-220 BC). {1-5}

True spade pieces probably appeared in the Eastern Zhou period (770-476 BC) and were followed by knife pieces, and then by round coins that are the prototypes of the cash coins issued practically unchanged in China and adjacent countries for over two thousand years. Finds show that spades, knives and early round coins often circulated together, suggesting that all were a tally for wealth if not an enabling medium of trade as such. Importantly, however: though round coins had appeared sporadically before, indeed were cast in many calligraphic varieties by the 350-220 BC Zhou and Liang States, their appearance in huge quantities of standard appearance begins with the first Empire and is clearly related to its administrative needs. {1-5}

Cash coins are small change, and prices were often expressed in strings rather than individual coins. A string generally consisted of one thousand coins strung together by a cord through their square central holes, but that thousand could be varied according to the province and the commodity being purchased. Larger transactions commonly employed gold, silver or bales of silk, of course, but cash coins were essential to the peasantry, and a contented peasantry made for a peaceful and governable empire. {1-5}

Chinese History to the Northern Song Dynasty

From Neolithic roots, a complex bronze age civilisation arose on the north China plain soon after 2000 BC, one characterized by writing, metal-working, domestication of the horse, class stratification and a political-religious hierarchy ruling a larger area from a cult centre. Of the earlier Xia dynasty there is no certain archeological evidence, but the Shang dynasty (c. 1700-1046 BC) may have ruled from five successive capitals, and certainly employed religion and ritual to back its military supremacy. Around 1050 BC, the Shang were overthrown by the Zhou dynasty (1045-256 BC), which in turn fragmented in the Spring and Autumn period (771 to 476 BC) into rival states. The elaborate chivalry with which Zhou warfare was first conducted descended into blood-soaked barbarism in the following period of the Warring States (403-221 BC), only ending when the Qin finally overcame its rivals and created China's first empire in 221 BC. The emperor Shih huangdi imposed a centralised uniformity throughout the country, in currency, writing and administration, but is remembered less as a statesmen than as a ruthless tyrant who met criticism with summary execution, moved hundreds of thousands of prominent families from the provinces to his capital at Xianyang, burnt books that were not simply practical manuals on agriculture, medicine or divination, and subjected millions to hard labour in constructing his palaces and the Great Wall. {6-11}

The first empire fell apart on the death of Shih huangdi but was followed by the joyous and outward-looking Western Han dynasty (206 BC- 220 AD). The arts flourished, Chinese suzerainty was extended to central Asia, and the examination system introduced to select and train administrators. {6} The Han dynasty was founded by Liu Bang (temple name, Gaozu), who assumed the title of emperor in 202 BC. Eleven members of the Liu family followed in his place as effective emperors until the dynastic line was challenged by Wang Mang, who established his own regime under the title of Xin until AD 25. The Eastern Han dynasty continued with Liu Xiu (posthumous name Guangwudi), and thirteen descendants who ruled until 220, when the country split into three separate kingdoms. Chang'an (modern Xi'an) was the capital of the Western Han empire, and Luoyang of the Eastern Han. {6-11}

From the disorders and many rival states and kingdoms that followed the collapse of the Han dynasty rose the splendid Tang dynasty (AD 618-907), renown for its poetry and extension of the examination system. The structure of the new central administration resembled that of Wendi's time, with its ministries, boards, courts, and directorates. Local government in early Tang times had a considerable degree of independence, but each prefecture was in direct contact with the central ministries. In the spheres of activity that the administration regarded as crucial — registration, land allocation, tax collection, conscription of men for the army and for corvée duty, and maintenance of law and order — prefects and county magistrates were expected to follow centrally codified law and procedures, but could interpret the law to suit local conditions. {6-11}

In the succeeding Song Dynasty (960-1279) — shrinking to the Southern Song when the north was lost to Jurchen tribesmen — Chinese society reached its apogee of wealth and refinement. Its founder, Taizu, stressed the Confucian spirit of humane administration and the reunification of the whole country. He took power from the military governors, consolidating it at court, and delegated the supervision of military affairs to able civilians. A pragmatic civil service system was the result, with a flexible distribution of power and elaborate checks and balances. Each official had a titular office, indicating his rank but not his actual function, a commission for his normal duties, and additional assignments or honours. Councillors controlled only the civil administration because the division of authority made the military commissioner and the finance commissioner separate entities, reporting directly to the ruler, who took the important decisions. In doing so, he received additional advice from academicians and other advisers who provided separate channels of information and checks on the administrative branches. Similar checks and balances existed in the diffused network of regional officials. The empire was divided into circuits, which were units of supervision rather than administration. Within these circuits, intendants were charged with overseeing the civil administration. Below these intendants were the actual administrators. These included prefects, whose positions were divided into several grades according to an area's size and importance. Below the prefects there were district magistrates (subprefects) in charge of areas corresponding roughly in size to counties. {6-11}

Song Economic Life (960-1279 AD)

Readers who imagine that no alternative exists to capitalism, should consider Song China, incomparably the richest, most diversified and best-governed economy of its time. China trade stretched across the world: to islands in the south-east Pacific, to India, to the Middle East and to east Africa. The ships were large, stoutly constructed and employed maps and compasses. Wealthy merchants and landowners strove to educate their sons for entry into government service, the upper echelons of which were lavishly rewarded. Industry was equally dynamic. Per capita iron output rose six-fold between 806 and 1078, and China may have been producing 125,000 tones/year by 1078. Copper sufficient to cast 6 billion cash coins/year in 1085 came from numerous small mines, of which some fifty alone were shut down between the years 1078 and 1085. {23} All mining, smelting and fabrication of iron, steel, copper, lead, tin and mercury were government monopolies, though some competition was later allowed the private sector, with beneficial results. Coal replaced charcoal as the country was stripped of its forests. Steel was used for armour, swords, spears and arrowheads, but most went into agricultural implements, notably the plough. Cotton was grown in central China, tea and sugarcane plantations increased, and Suzhou became famous for its silk production. Towns and cities saw a bustling commercial life. There were 50 theatres alone in Kaifeng, four of which could entertain audiences of several thousand each. The pleasure districts — where stunts, games, theatrical stage performances, taverns and singing girl houses were located — were packed with food stalls that stayed open virtually all night, and there were also traders selling eagles and hawks, precious paintings, bolts of silk and cloth, jewelry of pearls, jade, rhinoceros horn, gold and silver, hair ornaments, combs, caps, scarves, and aromatic incense. {12-18}

The government set social norms by defining crimes and their punishment; it anticipated crop failures and provided relief measures; it encouraged hygiene, public medicine and associated philanthropies; it recruited and tested public officials; it constructed and maintained roads, canals, bridges, dikes, ports, walls and palaces; it manufactured matériel and armaments; it managed state monopolies and mines and supervised trade. The numbers were large. In a population reaching 120 million, over 1 million belonged to the army and some 200-300,000 registered as civil employees (of whom 20,000 were ranked as officials). Most taxes were paid in kind, but payment by money increased throughout the dynasty, probably reaching a quarter to a third of the government's revenues. Larger transactions employed silver ingots and bolts of common silk cloth, and merchants issued notes of credit, at first privately but soon taken up the government. Factories were set up to print banknotes in the cities of Huizhou, Chengdu, Hangzhou, and Anqi, and were often large: that at Hangzhou employed more than a thousand workers. Issues were initially for local use, and were valid only for 3 year period. That changed in late Southern Song times when the government produced a nationwide standard currency of paper money backed by gold or silver. Denominations probably ranged from one string of cash to one hundred strings (each of a thousand coins odd). {12-18}

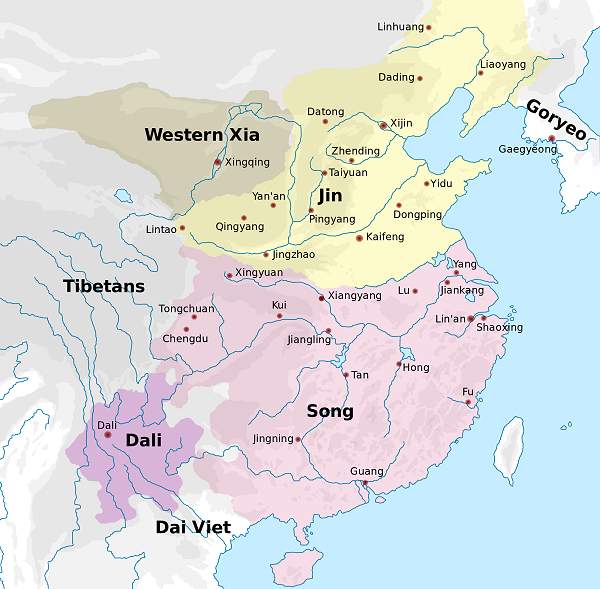

The Song was not a military state, but the army was nonetheless large and well-trained, latterly in new techniques. The Song could also put to sea a formidable navy. Nonetheless, it was diplomacy that China traditionally preferred, binding surrounding powers by treaty and tribute systems. That statesmanship went sorely amiss when the Northern Song allied themselves with the Jurchen tribesmen to conquer the threatening Tibetan Liao dynasty in 1125 (shown as Western Hsia in the map above). When the Song quarrelled over the division of spoil, the Jurchen promptly invaded northern China, and took the young emperor, his father Huizong and most of the court into captivity. Though they were never released, ending their days staring at forests and wild tribesmen, a scion of the family did evade capture to found the smaller Southern Song state. The Jurchen occupied northern China as the Jin regime, which gradually became sinicized. The reduced Song made Hangzhou its capital, when court life regained its old splendour and sophistication. All three kingdoms — the Liao, the Jin and the Song - were eventually overrun by the Mongols, who founded their own Chinese dynasty, the Yuan, in 1279. {12-18}

Northern Sung Calligraphic Variations

Cash coins of the Northern Sung dynasty employed six styles of calligraphy:

|  |  |  |  |  |

Seal Script | Orthodox | Clerkly Orthodox | Slender Gold | Running Hand | Grass Writing |

|

All these calligraphic types show variations that can run into many tens or even hundreds per issue. Those illustrated above are one cash coins of the Emperor Hui Zong (1101-25) and read Shen Song yuan bao (i.e. the reign name of the 1101-06 period) in running script. Gorny {19} lists only 10 varieties, but the author's collection had 35. The variations probably represent mint controls, each indicating a particular mint and year, but the details have been lost. {2}

The cash coins of the Southern Song are a more regular series, though sometimes less well made. The emperor used the one period title throughout. The year of the reign and sometimes the mint are shown on the reverse. The previous calligraphic variations are much reduced or absent.

Chinese Calligraphy

Confucians stress the personal qualities in correct behaviour, and this is no better reflected than in calligraphy, which is held in the highest regard — in everyday correspondence, in official documents, in painting and coinage.

The earliest logographs (used in the Shang, but originating in the late Neolithic Longshan culture of 2600-2000 BC) were engraved on the shoulder bones of large animals and on tortoise shells. This jiaguwen (oracle bone script) was followed by a form of writing found on bronze vessels associated with ancestor worship and so known as jinwen ('metal script'). This bronze script became universal when China was unified in the 3rd century BC. Xiaozhuan ('small seal') script followed, characterized by lines of even thickness and many curves and circles, and probably developed to meet growing demands for record keeping. Each word tends to fill up an imaginary square, and a passage written in small-seal style has the appearance of a series of equal squares neatly arranged in columns and rows, each of them balanced and well-spaced. Because this small seal script cannot be written quickly, a fourth style was devised: the lishu, or official style. Squares and short straight lines predominate, but vary in thickness. To allow for artistic variation, a fifth style gradually evolved: the zhenshu or regular script, which is still used for books and government documents. Finally, in the xingshu, or running script, even these controls were relaxed, and the Northern Song coinage in particular displays a wide range of individual hands, often beautiful and verging on abstraction.

For millennia calligraphy has been an art form. The combination of technical skill and imagination, acquired by laborious practice, must provide interesting shapes to the strokes and create beautiful structures from them without any retouching or shading. Most important of all, there must be well-balanced spaces between the strokes. The fundamental inspiration of Chinese calligraphy, as of all arts in China, is nature. In regular script each stroke, even each dot, suggests the form of a natural object. As every twig of a living tree is alive, so every tiny stroke of a piece of fine calligraphy has the energy of a living thing. Printing does not admit the slightest variation in the shapes and structures, but strict regularity is not tolerated by Chinese calligraphers. A finished piece of fine calligraphy is not a symmetrical arrangement of conventional shapes but something like the coordinated movements of a skillfully performed dance — impulse, momentum, momentary poise, and the interplay of active forces combining to form a balanced whole. {42}

Chinese Use of Paper Money

Cash coins are cumbersome, and required large quantities of copper, lead and zinc. In 1073, for example, the Northern Song issued some six million strings of cash, each containing a thousand coins. The Northern Song alone issued over 200 million strings of coins, many of which found their way to inner Asia, Japan, and south-east Asia, where they often became the preferred coinage. China had numerous copper mines in Yunnan {1} and elsewhere, but the output was small, and overseas supplies never to be counted on. Cash also leaked across borders in small trading transactions, for all that iron, and sometimes lead, coins were issued in peripheral provinces, and exotic imports largely balanced by the demand for Chinese silks and ceramics. Metal was also lost through the practice of burying coins with the dead to pay their passage to the other world. {23-24}

Paper notes were therefore replacing cash in burials in the 6th century, and bearer notes (hequan) began to be used by merchants for long distance trade in later Tang times: traders deposited valuables with corporations and were issued bearer notes that could be redeemed as needed. The authorities were not slow to extend the idea, and merchants were encouraged to deposit metallic currencies with the Government Treasury in exchange for official 'compensation notes', called fey-thsian or flying money. Indeed the continuing metal shortages, and the sheer volume of cash coins required for a booming economy during the Song dynasties, obliged the authorities to issue notes, which became a government monopoly in 1024. Paper money also overcame problems of local and incompatible currencies, though it led to further flights of metal overseas. Prices were quoted in paper money terms, which caused price inflation at times, particularly in the Southern Song, when it became profitable to melt down cash to make copper utensils and musical instruments. {26}

Generally, at least in Northern Song times, the paper currency was fully redeemable and the experiment was a success, indeed was vital in avoiding the deflationary effects of metal shortages. During the following Yuan dynasty, however, coin output was small, or its use even banned, and paper money made the only legal tender. Because these issues of the paper money were nation-wide, however, and were not backed by metal, there were continuous crises of confidence and periods of rapid inflation. {2, 26}

Inflation continued in the early Ming dynasty, and paper issues were suspended in 1450, although notes remained in circulation until 1573. Only in the very last years of the Ming (1643-4), when the capital was threatened by the Manchu, was paper money reissued. Generally the Ming used a private system of currency for important transactions. Silver, originating overseas, began to be used as a currency in Guangdong province, and from there the custom had spread to the lower Yangtze region by 1423, when it became legal tender for payment of taxes. All provincial taxes had to be remitted to the capital in silver after 1465. Salt producers had to pay in silver from 1475, and then corvée exemptions from 1485. Silver was supplied by overseas trade, being mined in Europe and the New World, and thence making its way in complex network of transactions across Europe and Asia, or more directly from Spanish possessions in the Philippines. This silver was not minted, however, but cast as ingots (sycee or yuanbao) weighing a nominal liang (about 36 grams) although purity and weight varied from region to region. {2, 26}