Volume One

Ancient and Medieval States

Background

First Empires

Coinage coincides with the growth of armies, and of taxation to pay them, in China, India and Europe. Chinese knives, spades and round coins only appear in any quantity during the Period of the Warring States. Not coincidentally, it was also the period of philosophers, who countered Legalist arguments that states needed strong laws resting on military coercion. The philosophers tried to put back what materialists had banished: the spiritual nature of man. Mo Di noted that the costs of warfare outdid its benefits, and Confucius spoke of benevolence and righteous behaviour. Cold calculations of cost and benefit that underlie societies first employing coinage divorce man from his larger nature, therefore, requiring the spiritual dimension to be rationally re-conceived in material entities (religion and philosophy) and also that the coinage should itself embody conspicuous trust, i.e. features demonstrating that the coins could indeed be used to pay taxes, public fees and legal penalties. Coins came therefore to represent power, authority and authenticity in their inscriptions, fashioning, symbolism and — in India and the near east — their use of precious metal. {1}

Writers on warfare in early China are quite specific about the aims of warfare: it is waged for material gain. The same drive for profit underlay the war economies of other countries, though Kautilya dressed the matter up in morality and justice. Thucydides likewise spoke of honour and national prestige in debating the massacre of the Melians who had refused to pay their dues to the Athenian empire, but the economic consequences of allowing the empire to fragment in this way were also perfectly clear. {1}

That close connection of coinage with war and slavery, David Graeber sees as an inevitable component of successful foreign policy in these harsh times. Wealthy Phoenician cities, pacific in nature and slow to issue coins in the face of growing hostility from Babylon, the Greek city states and Rome, were one by one destroyed. When Sidon was taken by the Babylonians, some 40,000 inhabitants committed suicide. The silver needed to pay Alexander's mercenary armies was looted from Achaemenid treasuries, and those armies, when they destroyed Sidon in 322 BC, sold 30,000 of its inhabitants into slavery. At the end of the Punic Wars, when Rome finally eliminated its old foe, Carthage was levelled and some hundreds of thousands were killed, raped or sold into slavery. Coins were widely employed in trade, of course, but may have originated in darker and more compelling needs. {1}

Achaemenid Empire (550-330 B.C.)

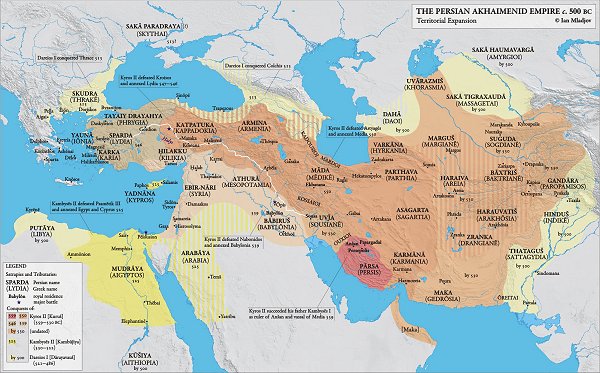

Though the Achaemenid Empire is often seen through Greek eyes as an Asian tyranny bent on extinguishing European ideals of independence and democracy, Persia was in fact a triumph of statecraft, one that created the largest empire the ancient world had seen, and brought together lands extending from Egypt to northern India under one government. Its inception dates from 550 BC, when Cyrus I of Persia (r. 559-530 B.C.) defeated King Astyages of Media and annexed Iran and eastern Anatolia. The Lydians of western Anatolia, allied with the Babylonians and Egyptians, counter-attacked under King Croesus, but their defeat led to Persia's rapid conquest of the Middle East, and subsequently of Egypt by Cyrus' son Cambyses in 525 B.C. {2}

When Cambyses died en route to Persia, Darius I (r. 521-486 B.C.) emerged as king. He promptly set about centralising government, building roads and palaces, but also appointed satraps (governors) that enjoyed considerable autonomy. Revolts of the Ionian city states brought him into collision with the Greeks in 498 B.C. The erring states were re-incorporated into the empire four years later, but not mainland Greece, which defeated the Persian forces at Marathon in 490 B.C. {2}

Darius' son Xerxes (r. 486-465 B.C.) tried to bring mainland Greece into the empire, but his large armies were outwitted by guerrilla tactics. Though the Spartans were defeated in battle and Athens sacked, the resourceful Greeks won a naval victory at Salamis in 479 B.C. Xerxes was then obliged to quell a Babylonian uprising, and the Persian army remaining was defeated by the Greeks at the Battle of Plataea in 479 B.C. {2}

Xerxes seems to have been assassinated. His son Artaxerxes I (r. 465-424 B.C) had to crush revolts in Egypt and establish garrisons in the Levant. The empire remained intact under his successor, Darius II (r. 423-405 B.C), but Egypt regained its independence under Artaxerxes II (r. 405-359 B.C), to be later reconquered by Artaxerxes III (r. 358-338 B.C). When he was assassinated, as was Artaxerxes IV (r. 338-336 B.C.), the throne fell to Darius III (r. 336-330 B.C.), a second cousin, who faced the armies of Alexander III of Macedon. Fortune and superior Greek hoplite armies finally won the day for Alexander, but on his early death the conquests were divided between generals, and Archaemenid lands became the Hellenistic kingdoms of the Ptolemies, Seleucids and Indo-Greeks. {2}

Life in the Achaemenid Empire

| About social life in the Achaemenid times we know very little, but it seems to have retained its mix of local cultures and languages. Traditionally, Persian society had three classes — a warrior aristocracy, a priesthood, and a labouring class of farmers and herdsmen, and to this structure was added a patriarchal tribal lineage, and no doubt the social distinctions of the peoples conquered. Royal inscriptions were trilingual, in Old Persian, Babylonian and Elamite, but most subjects remained illiterate.{3-5} |

Achaemenid Empire: Darius II — Artaxerxes II ( 423 — 359 BC). Au Daric, ca. 400 BC. (8.27 g, 17 mm). Obverse: | In art and religion the Achaemenid rulers were eclectic, local varieties being allowed while they assumed overall administration of the empire. The Zoroastrian calendar was adopted by Artaxexes I, for example, but other religions, and possibly various strains of Zoroastrianism seem to have been tolerated, at least for periods locally. {3-5} |

| It is for their splendid palaces that the Achaemenids were celebrated. Materials, styles and craftsmen were drawn from all quarters of the empire, and the eclectic mix moulded into a distinctive Persian taste for sophisticated exuberance. The Achaemenids were also great craftsmen in tableware, jewellry, weapons and pottery. {4} Agriculture was the mainstay of the empire, but equally important was the large and well-trained army, the law and government devolved to satraps, the last tending to become independent and indeed hereditary rulers. The first armies were tribal levies, but these were soon replaced by professional corps, led by the '10,000 immortals', 1,000 of whom formed the king's personal bodyguard. {4} |

Reverse: incuse punch. (BMC 58) | Around the king gathered a court of powerful hereditary landholders, the upper ranks of the army, the harem, religious functionaries and the bureaucracy administering the empire. {4} |

Satrapy Coinage

The coins struck by the Achaemenid Empire itself are rather crude affairs: flattish lumps of high-quality gold (daric) or silver (siglos) just bearing the king's insignia on one side. {5-7} Coins proper are a Greek invention, and the concept returned from its westward dissemination in the coinage of the Persian satraps on the edges of the Achaemenid Empire, notably in Anatolia. The coins illustrated below employ Aramaic for their legends, but are Greek in design and execution. {9}

|  |  |

Tarsos. Ar stater of Mazaios, Satrap of Cilicia. 361/0-334 BC. Ar Stater 24 mm 10.77 g. Obverse: Baaltars seated left, torsos facing, holding grapes, grain ear, and eagle in right hand, sceptre in left. TN to left BALTRZ (Baaltars) in Aramaic to right, M below throne. Reverse: lion attacking bull. MZDI (Mazaios) above. Monogram below. (SNG Lev 106; SNG Bn-) {8-10} | Astyra, Ae11, struck under the Satrap Tissaphernes, c. 400-395 BC. 11 mm 1.83g. Obverse: Bare head right; TISSA beneath neck / ASTURH, Reverse: cult statue of Artemis Astyra facing, club to right. (SNG France 124A; Klein 253; Stauber Adramytteion {11} | Tarsus. Ar stater of Datames, Satrap of Tarsus, 378–372 BC.Obverse: King seated facing right Bow to right. TDNMU (Datames) to left.Reverse: probably Ana, standing nude and pointing to head of Tarkumuwa (Datamenes){12-13} |

References and Further Reading

Need the 13 references and 5 illustration sources? Please consider the inexpensive ebook.