Volume Two

Financial Meltdown

Inflation

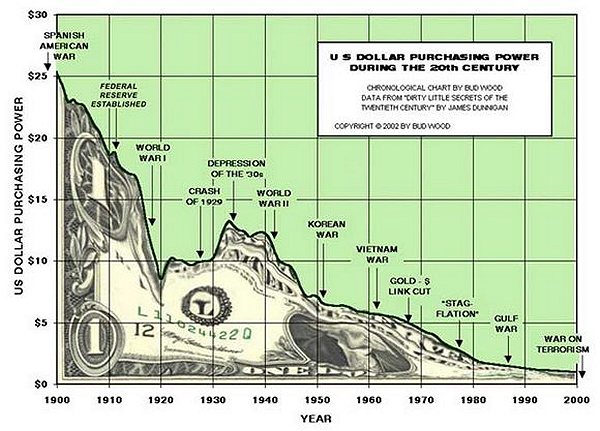

Inflation has been a feature of our economic life for a century or more, eating away at savings and reducing living standards of those on pensions and fixed incomes. To confound theorists and their explanations, the rates have fluctuated widely. The inflation rate is now comparatively low, but, even so, something purchased for US $1 in 1913 would now cost $24. Inflation is often modelled with those familiar supply and demand graphs questioned in the section on market theory, and many still argue for a natural rate of unemployment consistent with acceptable levels of inflation, for all that the Phillips curve applies better to the US than the UK economy. {1}

In theory, exchange rates adjust to reflect the buying power of currencies, but the matter is much affected by the complex inter-linkage of lending institutions, and the economic (and sometimes military) clout of the country concerned.

Matters are often difficult to predict. Prices in modern economies are not set by supply and demand, for example, but by monopolistic understandings at close to the point of maximum profits. Wage increases will cut into those profits, but increased wages may also swell their customer’s buying power. The business may be able to raise prices with product diversification, moreover, and/or find a new market sector. The entry into the market of a new, more innovative competitor will generally make for adverse effects, of course, attracting away better staff and providing stiffer competition. Price rises of raw commodities in an isolated market will be met by reduced consumption, but in most markets today the businesses will try to increase their prices, be forced into short-term borrowing and/or bring out cheaper quality lines. Overall it is innovation and new product lines that offset supply shocks, and that innovation also brings down prices. Compared to models available in 1983, for instance, computers today are a quarter of the price and ten thousand times more powerful. {2}

Government policies from the 1980s in Britain and the USA have generally targeted inflation rather than unemployment, reducing top rates of income tax, cutting the power of trade unions, and rewarding those managers that squeezed more from their workforces by handsome bonuses. While most employees have had to work harder for less, the top managers have enjoyed the means to acquire more assets: land, jewellery, company shares, etc. Banks have also been happy to advance loans to the new rich for such purposes, again fuelling asset inflation. Oil exporting countries were awash with petrodollars after the 1973 ‘oil shock’ moreover, which was a windfall for the banks and property markets, but saw little investment in goods and services needed by the middle and lower classes. The Thatcher and Reagan governments also flirted with Milton Friedman’s neoliberal concepts of money supply as a constraint on inflation, but quietly dropped the policies some three years later on finding money supply difficult to measure, and even more to control. Nonetheless, debt of all types has increased, the more so with the 1990 Iraq War, which was not covered by increased taxes or war bonds, and again with the rescue of big banks in 2008. After a decade of high levels in the 1980s, inflation has been brought down to acceptable levels, but at the cost of increased unemployment, inequality and debt levels. {2}

Much more dangerous than inflation is hyper-inflation, however, which may destroy the state altogether. We look at several instances below.

Roman Empire

Inflation was a constant problem in the Roman empire as the coinage was progressively debased, but historians recognize the late third century to mid fourth century as particularly threatening. The pay of the legionary soldier was 225 denarii a year under Augustus (31 BC-14 AD) but 500 denarii under Septimus Severus (193-211), when the silver content was only 60% of face value. Caracalla (211-17) raised that pay by 50%. The empire desperately needed funds to pay armies confronting mounting barbarian threats, and Caracalla replaced the denarius with the antoninianus, nominally worth 2 denarii, but not accepted as such. Under Gallienus (253-68) any pretence at sound money was abandoned, and the antoninianus became a bronze coin with the thinnest of silver washes. Nor was Aurelian's (270-75) revaluation of the antonianus to 5 denarii any more successful. Prices rose. A loaf of bread cost twice what it had a century before. Shop keepers would not accept the coins at face value, and money changers discounted them heavily. Worse still, the government would not accept its own coinage for tax payment, but insisted on being paid in kind. {9} With the loss of Dacian gold mines, gold coinage practically disappeared, being struck only as donations for troops. The result was unmitigated misery. In Egypt, for example, where 30 litres of wheat had cost 7/8 drachma in the second century, the same quantity cost 12-20 drachmas in the first half of the third century, and 120,000 by Diocletian's time (284-305). {3}

Inflation was a constant problem in the Roman empire as the coinage was progressively debased, but historians recognize the late third century to mid fourth century as particularly threatening. The pay of the legionary soldier was 225 denarii a year under Augustus (31 BC-14 AD) but 500 denarii under Septimus Severus (193-211), when the silver content was only 60% of face value. Caracalla (211-17) raised that pay by 50%. The empire desperately needed funds to pay armies confronting mounting barbarian threats, and Caracalla replaced the denarius with the antoninianus, nominally worth 2 denarii, but not accepted as such. Under Gallienus (253-68) any pretence at sound money was abandoned, and the antoninianus became a bronze coin with the thinnest of silver washes. Nor was Aurelian's (270-75) revaluation of the antonianus to 5 denarii any more successful. Prices rose. A loaf of bread cost twice what it had a century before. Shop keepers would not accept the coins at face value, and money changers discounted them heavily. Worse still, the government would not accept its own coinage for tax payment, but insisted on being paid in kind. {9} With the loss of Dacian gold mines, gold coinage practically disappeared, being struck only as donations for troops. The result was unmitigated misery. In Egypt, for example, where 30 litres of wheat had cost 7/8 drachma in the second century, the same quantity cost 12-20 drachmas in the first half of the third century, and 120,000 by Diocletian's time (284-305). {3}

Diocletian reformed the currency, striking substantial, indeed handsome, pieces in all three metals. The silver pieces were clearly marked as worth 5 denarii, as Aurelian's had been, but were twice the size. Gold was issued to an exact standard of purity, and even the silver pieces, worth in metal content less than their face value, were the best seen for a century. Yet the attempt failed. Gold, against which other denominations were measured, fluctuated in value as supply and demand dictated. The steepest inflation for 50 years occurred between 290 and 300. In 301-2, Diocletain issued an edict to fix incomes and prices, the latter for over 900 commodities. That too proved a failure: goods simply disappeared from the market. A pound of gold at the time was valued at 50,000 denarii. A decade later the valuation was 120,000, and 300,000 by 324. {3}

Whatever the misery for the great mass of Roman citizens, the army had to be paid. Gold donatives became an expected part of their pay, and these huge sums had to be raised by taxation. Many novel taxes were devised: an extraordinary income tax (crown money), indirect taxes, death duties and taxes on the liberation of slaves. When these were no longer remunerative — and they fell disproportionately on the already impoverished — soldiers were given free rations, clothing and raw materials for weapons. Provincial governors were ordered to supply such materials, and these orders were passed to landowners, who inflicted them on tenants. In Italy, and Rome in particular, these orders became an added drain on resources. Over one hundred thousand lived on hand-outs, and 80,000 people in Constantinople received food distributions under Constantine. {3}

A census was instituted, and the land measured out in units (iuga) from which a certain amount of crops could be expected. The expectations were applied uniformly, and adjusted annually, a striking example of state power.

Surprisingly, though that also failed, some notion of value persisted all the same. Land expectations were measured in cash values. Soldiers and government officials were paid in cash. And some taxes were still paid in cash. Those notions of value reappeared in the solidus issued by Constantine. It was a smaller coin than the aureus of Diocletian, but it was of high purity and produced in great numbers, the gold coming from war booty seized from the defeated Licinius, and later the melting down of statues in pagan temples. To assert the legal tender nature of the solidus, Constantine insisted that two new taxes be now paid in gold, and all rents from imperial estates. Few saw gold in their normal lives, of course, and the silvered bronze currency continue to depreciate at alarming rates. The 300,000 denarii to the pound of 324 rose to nearly 20 million by 337, and to 330 million twenty years later. Indeed the inflation spiral expressed in 'silver' steepened even further until the Byzantine emperor Anastasius (493-518) issued large bronze coins that the populace would final accept as legal tender. Much of the rural economy outside large estates would have resorted to exchange and barter in these terrible years, but the solidus — like the gold standard fifteen hundred years later — gave confidence in the state's powers, even as that state removed the last vestiges of individual freedom. {3}

New World Silver

Across Europe prices rose six-fold between the early 16th century and mid 17th centuries, an inflation level averaging 1-1.5% p.a. over 150 years. Though modest by contemporary standards, the inflation was not matched by comparable wage increases, and so caused hardship and civil unrest. The cause has traditionally been laid at the door of the large influx of bullion, particularly silver, from the New World mines in Bolivia and Mexico, coupled perhaps with the pressure on food prices by a population recovering from the Black Death. Food prices did indeed rise steeply during the epidemic that carried off a third of the work-force, but fell quickly afterwards when there were fewer mouths to feed, resuming an upward trend when agricultural land was not brought back into production. But inlation began three decades before the arrival of New World bullion in appreciable amounts, so that historians must now take into account other factors, particularly the south German mining boom and the increase in credit facilities. The first started in the late 1450s and reached its peak in the 1530s. Yet that silver was largely exported to the Levant in exchange for gold and Asian luxuries, at least till 1515-29, when Ottoman expansion closed these routes and diverted silver to the Antwerp market for shipment out of Europe. Even northern countries like England suffered silver shortages, and smaller families had sometimes to melt down their silver plate to pay taxes that demanded payment in metal. The more prosperous families escaped these problems, however, and were able to use nascent banking facilities to enclose lands, improving their yield but also adding to the dispossessed for whom new (and savage) laws of vagrancy were devised. {4}

Across Europe prices rose six-fold between the early 16th century and mid 17th centuries, an inflation level averaging 1-1.5% p.a. over 150 years. Though modest by contemporary standards, the inflation was not matched by comparable wage increases, and so caused hardship and civil unrest. The cause has traditionally been laid at the door of the large influx of bullion, particularly silver, from the New World mines in Bolivia and Mexico, coupled perhaps with the pressure on food prices by a population recovering from the Black Death. Food prices did indeed rise steeply during the epidemic that carried off a third of the work-force, but fell quickly afterwards when there were fewer mouths to feed, resuming an upward trend when agricultural land was not brought back into production. But inlation began three decades before the arrival of New World bullion in appreciable amounts, so that historians must now take into account other factors, particularly the south German mining boom and the increase in credit facilities. The first started in the late 1450s and reached its peak in the 1530s. Yet that silver was largely exported to the Levant in exchange for gold and Asian luxuries, at least till 1515-29, when Ottoman expansion closed these routes and diverted silver to the Antwerp market for shipment out of Europe. Even northern countries like England suffered silver shortages, and smaller families had sometimes to melt down their silver plate to pay taxes that demanded payment in metal. The more prosperous families escaped these problems, however, and were able to use nascent banking facilities to enclose lands, improving their yield but also adding to the dispossessed for whom new (and savage) laws of vagrancy were devised. {4}

Few in Spain or Europe generally actually saw New World bullion either, as it was placed on arrival in warehouses owned by Genoese bankers, ready for shipment east. A revived China under the Ming dynasty had discontinued the use of paper money and required the silver which its own mines (and those of Japan later) could not supply. What the Genoese bankers provided were interest-bearing annuities that encouraged unrealistic Spanish dreams of conquest, as the notes could endlessly multiply the actual value of the bullion, which was anyway considerable, often amounting to 20% of Spain's revenues. The bills circulated at a discount, and were traded at large fairs like that of Medina del Campo outside Seville, constituting an early form of bank notes, which paid for troops in the Netherlands and Italy, built a large navy and maintained forces in Germany, and increased consumer demand at home. Much went into court spending and lavish display, but the notes were also used in the town and countryside, putting up food prices and making Spanish manufactures uncompetitive. Charles V fell heavily in debt to banking firms in Florence, Genoa and Naples, and Philip II outright defaulted on his debts. {4}

The Weimar Republic Hyper-Inflation

With hindsight, the causes of the runaway inflation of the Weimar Republic are clear enough: the heavy reparations imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, under which the country was required to pay sums amounting to three times the value of its land and industry. Since reparations had to be paid in hard currency, and the country could not borrow such sums outright, and had indeed come off the gold standard, the only strategy left was to keep printing marks and hope to keep ahead of their rapidly depreciating value on foreign exchanges. {5}

With hindsight, the causes of the runaway inflation of the Weimar Republic are clear enough: the heavy reparations imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles, under which the country was required to pay sums amounting to three times the value of its land and industry. Since reparations had to be paid in hard currency, and the country could not borrow such sums outright, and had indeed come off the gold standard, the only strategy left was to keep printing marks and hope to keep ahead of their rapidly depreciating value on foreign exchanges. {5}

Parties to the Versailles Treaty had different motives. France wanted security and intended a weakened Germany, a country demilitarised and unable to repeat its 1870 and 1914 aggressions. Britain wanted reparations to continue at more moderate levels, afraid that France, by invading Germany to extract payment in kind, would upset the power balance in Europe. American banks saw Germany as a bulwark against the spreading contagion of communism, and quietly continued to fund large Germany businesses up to, and sometimes through, the Second World War. {5}

The tragedy had several components. Expecting a speedy war, Germany had borrowed rather than impose an income tax to pay for armaments, which had depressed the value of the mark: it had fallen throughout the war from 4.2 marks to 8.9 marks to the dollar, and continued falling thereafter. The new Weimar Republic was not strong enough to impose punitive taxes to pay for what seen as demonstrably unfair, and ran unbalanced budgets, which depressed the mark further. Industry was unscathed by war, however, and with its well-trained workforce might well have turned Germany into the powerhouse of Europe again. And the interim 20 billion gold marks was perhaps achievable. But in 1921 came the 'London ultimatum', demanding reparations amounting to 132 billion gold marks (50 billion in gold marks plus 26 percent of the value of Germany's exports). The mark plunged further, and the country suffered more civil unrest, political assassinations in extreme left and right wing parties, and loss of business confidence. As inflation took hold — the July 1914 wholesale price index measured 100 in July 1922, 194 thousand in July 1923 and reached the meaningless 726 billion figure in November 1923 — coins became worthless, and barrow-loads of bank notes were needed for everyday purchases. {5}

Though unemployment initially remained low, living standards fell, and food itself became scarce. Pensioners and those living off savings were rendered destitute. The rich, faced with high taxes and declining wealth, spent prodigally, which only fuelled class animosities. The industrialists survived well enough, though even these were sometimes bankrupted when the mark fluctuated too wildly, confounding their business plans. In the crucial summer of 1922, the government itself took an unhelpful break from the turmoil, and note printers went on strike. But that hardly mattered: official currency was practically worthless, and businesses paid wages on account or issued their own IOUs. Anyone who could do so naturally sold their depreciating currency as fast as possible. Many speculated, and the Reichsbank, ostensibly the State bank but in fact private and driven by commercial interests, facilitated that speculation by offering easy loans. Investors sold the mark short, i.e. bet on its decreasing value by borrowing at one conversion rate and returning the 'loan' by currency 'purchased' at a lower rate, so pocketing the difference. Such puts and calls are an entirely legal transaction, of course, being widely used to protect companies from adverse currency or commodity price swings, but here the device was distinctly unhelpful to the country, and soon other banks were lending for the same purpose, accelerating the mark's downward spiral. In January 1923, determined that something should be paid, even in kind, France and Belgium invaded the Ruhr, Germany's key industrial area accounting for 85% of its coal production, 80% of its iron and steel manufacture and 70% of its traffic in goods and mineral. Ruhr workers promptly went on strike, preventing reparation payment altogether, but also adding to Germany's creeping unemployment problems. Amid despair and civil unrest, the German Chancellor declared a state of emergency and put the country under military rule. {5}

Inflation came to an end in 1923 when the Reichsbank was put under strict regulation, a new denomination issued, and easy access to loans eliminated. The new denomination, the Rentenmark, was ostensibly backed by hard assets — agricultural land and industrial plant — and issues strictly limited. Twelve zeros were removed from prices in the old currency. Nonetheless, the old currency continued in circulation, and in November 1923, one US dollar was worth 4,210,500,000,000 Reichmarks. A year later the denominations had fallen further, to a third of their agreed exchange rate with the Rentenmark. But the situation slowly righted itself. An exchange rate of one trillion to the Rentenmark was agreed, debts, government loans and mortgages restructured in the new currency, the rates being based on the US dollar and the wholesale price index, and their legality established in court. {5}

But immense damage had been done, and the episode still casts a long shadow over current EEC policy. Europe had become another country, and one where American banking power was clearly important. The Rentenmark was called a 'confidence trick', but it was confidence that German industry desperately needed, and in this the Dawes Plan, under which Germany borrowed from American banks, may well have helped. In a deal that owed much to the American financier J.P. Morgan, the first four years (1924-9) would see the country loaned $800 million, repaid by modernized industrial output. Unfortunately, the attached guarantees allowed Germany to once more live beyond her means, and indeed many companies were being lavishly rebuilt when the 1929 New York stock exchange crash ended loans, and the country returned to economic turmoil. {5}

Foreign trade declined as countries retired into protectionism. Worse still, austerity was imposed by Chancellor Brüning’s programme of spending cuts and tax increases. German unemployment climbed from 1.3 million in 1929 to over 6 million in 1933. Average real incomes fell a third as economic misery and criminality increased. But banking is an international community, and Germany's problems were soon part of a larger picture. Between 1924 and 1931, German federal debt increased 6.6 bn marks, and German local government debt went up 11.6 bn marks. Foreign debt, excluding reparations, amounted to 18.6 bn marks. After 1930, however, foreign loans were practically unobtainable, and a flight from the mark caused a great drain of German gold reserves. Business dwindled as the money supply dried up, and unemployment became a burning political issue. German banks themselves came under pressure, having to call in reserves from London banks as customers withdrew deposits to survive. These actions in turn drained British gold reserves. As Britain had re-embraced the gold standard, i.e. the money supply had to be matched by gold reserves, German deflation spread to Britain as the reduced money supply restricted loans, in turn causing businesses failures and unemployment. Faced with a loss on its extensive British investments, America arranged a one-year moratorium on reparations, but on terms that proved unacceptable to Germany. At the Lausanne Conference of June 1932, German reparations were cut to 3 bn marks, but the agreement was not ratified because the US Government refused to cut war debts in equal measure. {5}

The economic misery brought the Nazis to power, and in 1933 Hitler simply repudiated reparations. In all, Germany had paid 21 billion marks and borrowed nearly 19 bn as overseas loans. Contrary to prevailing economic theory, then and now, the Nazis turned the country round by having an independent monetary policy and instituting a full-employment public-works program, even before appreciable armaments spending began, though the anticipated expansions certainly convinced businesses that government promises would be kept, and so sustained the recovery. In four years a ruthlessly authoritarian and autarkic state built the strongest economy in Europe. {5}

There, according to mainstream economists and historians, the alarming tale of Weimar inflation ends, in wavering returns to business confidence. Contrarian historians, however, see the matter much more in terms of individuals and underlying, camouflaged, commercial policies. Though these views are commonly dismissed as ‘conspiracy theories’ they have their documentation and do fill many gaps in our understanding. The devastating importance of war reparations is not denied, but both the Weimar inflation and the rise of the Nazis were consciously engineered by banking interests in Britain and America, who sought to gain control of financial and political events in Germany. {5}

Towards the end of W.W.I, which the Axis powers looked likely to win, some $8 bn were owed by the Allies to American banks, who then started a massive propaganda exercise to bring America into the war and recover their threatened loans. Reparations were then purposely made excessive, by France, Britain and America to check the industrial potential of Germany, but the American banks quietly waited until the French occupation of the Ruhr had failed before launching their Dawes Plan that would render Germany industry, the second-largest in the world, entirely dependent on US interests. That lifeline was severed when American banks were caught up in the Great Depression and Britain came off the gold standard in 1931, but, through intermediaries, notably Thyssen and I.G. Farben, the Nazis were secretly funded and enabled to become the second largest political party in Germany. Schacht was made head of the Reichsbank once again, Germany obtained a loan of $2 bn from Britain, Standard Oil built oil refineries in Germany, and that country also took secret delivery of American aircraft production machinery. Some US bank funding continued through W.W.II. as the underlying aim was to replace London banking supremacy with Wall Street’s, achieved when a victorious Britain had to pay back American loans after the war. The Marshall Plan was a generous offer, but also kept Europe within the American sphere of influence, dependent on NATO and serving as a growing market for American manufactures. {5}

Zimbabwe

Money is a hard-hearted affair, and disaster can come from the most laudatory motives. In 1998, the Mugabe government of Zimbabwe expropriated land owned by white farmers, who had largely acquired their disproportionate holdings under colonial rule. Unfortunately, the new recipients had no knowledge of farming, or indeed much interest in the work. Food production fell disastrously, and unemployment climbed to 80%. Food had to be imported, depleting foreign currency reserves that were otherwise needed for capital items in transport, mines and businesses. All declined in their turn, and lack of maintenance prevented railways carrying mineral products to the coast for export. Austerity, or radical reduction in living standards, is the prescribed remedy, but one that was politically unacceptable: people would have starved. {6}

Money is a hard-hearted affair, and disaster can come from the most laudatory motives. In 1998, the Mugabe government of Zimbabwe expropriated land owned by white farmers, who had largely acquired their disproportionate holdings under colonial rule. Unfortunately, the new recipients had no knowledge of farming, or indeed much interest in the work. Food production fell disastrously, and unemployment climbed to 80%. Food had to be imported, depleting foreign currency reserves that were otherwise needed for capital items in transport, mines and businesses. All declined in their turn, and lack of maintenance prevented railways carrying mineral products to the coast for export. Austerity, or radical reduction in living standards, is the prescribed remedy, but one that was politically unacceptable: people would have starved. {6}

As always, the picture is a little more complicated, with blame attaching to several parties. The Republic of Zimbabwe was created from the former British colony of Southern Rhodesia in 1980, and initially did well, particularly in wheat and tobacco production. But between 1991 and 1996, the Zimbabwean Zanu-PF government embarked on the usual Economic Structural Adjustment Programme (ESAP) recommended by the IMF and the World Bank, which led to an immediate rise in the inflation rate. The Mugabe government blamed the IMF for the problems, but was in fact quietly printing money to finance wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In the unrest that followed, in the late 1990s, the government began redistributing land to Zanu-PF fighters, who had no experience or training in farming, which led firstly to EU and American economic sanctions being applied to the country, and secondly to falls in food output and then in other sectors. Between 1999 and 2009, outputs fell as follows: food by 45%, manufacturing by 26-29%, and employment by 80%. The sanctions were serious — asset freezes, visa denials, and travel restrictions — and the Government, refused an IMF loan in 2001, took to printing its own money, declaring price rises illegal, and continuing to pay government workers in depreciating Zimbabwe dollars. The banking sector collapsed, and with it the confidence in the government as inflation took off, reaching 11.2 million % p.a. in June 2008, when the Zimbabwe dollar was discontinued. Much business is now done on the black market, and Zimbabwe citizens use foreign currency, usually the American dollar, for everyday transactions. {6}

Debt Empires

If banking — with its arcane jargon, strange book-keeping habits of showing deposits as liabilities, and the confidence trick of issuing paper money on the unfounded assurance that all could be redeemed by gold — has an air of unreality, it is because the mental concepts are indeed hard to grasp. Many famous economists, Keynes and Galbraith among them, thought they were purposely kept so. How are bank loans conjured out of thin air? Why was Wall Street bailed out by printing money in the 2008 financial crash when homes and business of the innocent parties were not? What indeed is money now, a commodity or IOU? Economists generally call it neither, of course, but simply a 'neutral veil' obscuring more fundamental matters, for all that money most certainly buys political power and hence influence on economic policy. Moreover, if money is now a fiat currency, created by the powerful interests of banks and governments, with no more backing than a confidence in those institutions, what moral obligations underwrite our use of money when those institutions are found to be cheating, as they increasingly are? What happens, worse still, when the respected edifice of market economics is shown to be an elaborate charade, not simply 'backboard models' but a way of keeping citizens from a fairer division of the economic spoil? {7}

Such matters may seem remote from coinage, but coins are not simply tokens recording trade, and the face they show to the world, indeed their emergence at all, reflects deeper, more intangible but important realities. Spain's access to the silver wealth of the New World paradoxically made her poorer because the wealth was not invested but frittered away on wars and ostentation. For centuries the European denominations issued in gold and silver were continually being melted down when the face value of one fell below their contained metal when measured in terms of the other. The industrial revolution that largely created the modern world was only made possible by banking sleights of hand, and to many observers the austerity programmes imposed on EEC countries today are not only unnecessary, but represent a woeful and perhaps deliberate failure to understand how money really works. For Marxists at least, and probably others, credit is the monetisation of the future productive power of individuals, or whole groups of individuals. Banks do not lend money, theirs or anyone else's: they create money in the act of extending credit. That is the only way money is created, on the expectation that the borrower will work to pay back the principal, plus interest, the last being a time-based rental fee. {8}

How Debt Works

Loans attract interest, and interest, if not promptly paid, rapidly accumulates to sums impossible to pay off. Usury, the practice of making money out of money, has for 2,000 years proved much more lucrative than making or growing things. Religions have naturally castigated the practice, and rebellions have often centred on land redistribution as homes, families and persons were reduced to penury and worse. But if debt causes dangerous inequalities, it is something built into our contemporary money system. {9}

Suppose a prospective house purchaser borrows $100,000 as a mortgage from his local bank (bank A). Four things happen.

1. After assessing the risk, and establishing collateral (probably the house), Bank A creates the money 'out of thin air'. It does not allocate the deposits from other customers to this new loan, but simply adds a digital entry into its books, showing the $100,000 loan as an asset and the collateral as a liability.* By this method is money created, and by no other way (bar some 3% as notes and coins issued by the Mint). {10}

2. The loan of $100,000 is credited to the customer's bank account. The customer can then write a cheque for $100,000 against that account, and hand the cheque to the seller of the house. Suppose the seller pays the whole $100,000 into his own bank (bank B). If that bank must by law retain 10% assets to cover loans, some $90,000 will be available for new customer loans. Those loans are paid into bank C, that bank in turn will have 90% of $90,000 available for its own loans, i.e. $81,000. That sum can be further lent to other banks, and so on, the loans progressively diminishing. But that $90,000 plus $81,000 plus $72,900 plus . . . add up to an appreciable sum, in fact to $1000,000. By the fractional reserve requirement of 10%, some ten times the original loan is eventually lent out by the banking system. In short, the money supply is increased ten times. {11}

3. The prospective purchaser has to pay the interest on his mortgage, and must do so by his own efforts. If the interest itself amounts to $150,000, he must engage in competition with his fellow man to make this money and pay it 'back' to the bank, which has done nothing to earn it beyond some trifling paperwork (rationalized as risk and opportunity cost). Not only is the economic system inevitably competitive, but inflationary too, because that $150,000 has also to be created by banks as further loans. There is no other way of creating money. Although much contested and obfuscated, debt is what underlies our current money system. {12}

4. For loans not covered by its fractional reserves, a bank will borrow from the Fed or the money market, and so pay some modest interest on its own borrowing. The Fed in turn creates that loan 'out of thin air' by levying a loan on itself, and so increasing the money supply. {12}

If business is slack, and loans are not being sought, a bank will invest some of its reserves in safe government securities, again showing the investment as securities purchased and liabilities at the Fed.

(* Or more strictly as assets (loans + securities) = liabilities (deposits + securities + capital). Even that is much simplified. In practice, derivatives and inter-bank loans will enter into any major bank's assets and liabilities, an unstable situation that is on the rise. Deposits accounted for 73% of French bank liabilities in 1980, for example, but only 26% in 2011. Loans accounted for 84'% of assets in 1980, but only 29% in 2011. {13})

In practice, banks are not limited by their reserves, but will make loans regardless, simply borrowing the additional funds needed from the Fed or central bank at negligible rates of interest. Since the Fed conjures the additional by drawing on itself, i.e. out of the air, and the boundaries between commercial (which can make loans) and investment banks (which should not) is paper-thin and often ignored, banks can and do acquire businesses by making no more than a few key strokes in digital accounts. Banks are liable for bad loans, of course, but only advance loans against collateral that can be seized when loans turned sour. In their riskier gambles, moreover, the 'too-large to fail' banks have been further covered by bail-outs drawing on the tax payer: a surreal win-win situation.

Banking is also a competitive world, and banks must use their assets as productively as possible. Before the 2008 financial crash, the big banks took further risks, which can be summarized as: {12}

1. Reduced their collateral or fractional reserve to 3% or less, making them technically insolvent when a major loan went bad.

2. Created their own investment derivatives, often with subprime mortgages or 'casino' gambles, selling them to gullible clients worldwide. The derivatives were based on complex but often false market models. The derivatives were optimistically awarded a AAA rating, and given insurance cover by AIG and other large insurance agencies. Unfortunately, those insurance agencies lacked the assets to cover such large trades, and had their own assets complexly interlinked with the banks they were protecting, becoming as vulnerable to risk as the banks themselves.

3. Got legislation (Glass-Steagall Act) repealed that formerly separated commercial and investment banks, so enabling investment banks to create derivatives that involved everyone's money.

4. Evaded legislation by operating 'shadow' accounts, where transactions were kept off the books. In time, these accounts became too complicated even for management to understand properly.

Rates of Interest

Critical to loans being affordable, and so beneficial to business, is the rate of interest. International capital is mobile, and quickly drains from countries offering good returns to those offering even better, often leaving a trail of havoc in its wake: wrecked societies, industries and currencies. High interest rates prevent many needed investments in underdeveloped countries from going ahead, and oblige long-term projects offering steady employment and development opportunities to morph into short-term plunder of the environment. Mines have to be high-graded, timber extracted without reforestation, and large-scale agriculture practised without regard for local needs. Before banking was deregulated in the 1970s, and so made free to charge exorbitant rates for risky but lucrative (generally financial) ventures, the rate of interest had been falling. Indeed the return on British investments fell from 6-8% in 1700 to 3% in 1751, and that 3% proved sufficient to launch the agrarian and industrial revolutions that transformed Britain's place in the world. Low rates favour business and enterprise generally, but not the rentier class that banks represent and governments increasingly serve. The larger banks today have more financial clout than medium-sized countries, and with the failure to regulate credit and interest rates has come a widespread distrust of government and the democratic system altogether. Even if governments were truly elected to represent their informed citizen's interests, those governments would in practice, and of necessity in today's world, remain subservient to the financial institutions. {13}

Compound Interest

If interest on a loan is not repaid, that interest is added to the capital loaned, and builds up exponentially — slowly but remorselessly. Had, for example, the Indians who sold the island of Manhattan for $24 in 1626 invested the money in an account yielding 8% compounded annual interest, the account today would be sufficient to buy back all Manhattan, with several trillion dollars left over. Totals over longer intervals are even more intimidating. A single penny saved at 5 percent interest at the beginning of the Christian era, compounded annually, would by the eighteenth century have earned equivalent to a solid gold sphere 150 million times bigger than the Earth. {14}

That picture is unreal, but there is nothing imaginary in the debt hanging over our contemporary economies. {14}

|

| External Debt (US$ trillion) | External Debt as % of GDP | As of Date |

| USA | 19.7 | 106% | 2018 |

| China | 11.3 | 50% | 2018 |

| India | 2.3% | 70% | 2018 |

| Japan | 9.1 | 238% | 2018 |

| Germany | 4.0 | 60% | 2018 |

| France | 2.7 | 97% | 2018 |

| UK | 2.8 | 87% | 2018 |

| Russia | 1.1 | 15% | 2018 |

| Portugal | 0.3 | 121% | 2018 |

| Ireland | 0.3 | 67% | 2018 |

| Brazil | 2.0 | 88% | 2018 |

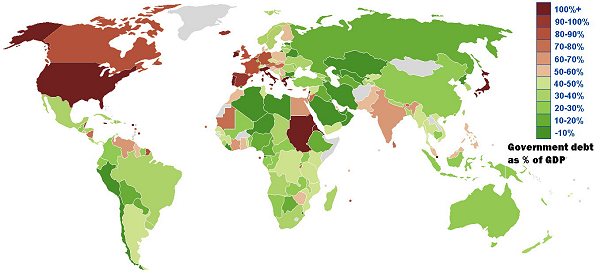

Like banks, lenders will continue making loans at favourable rates while there is every prospect of loan being repaid, i.e. the economy is thriving and under no external threats. What percentage is critical? A World Bank study found that debt to GDP ratios over 77% start dragging down economies, Every percentage point above this figure will cost developed countries1.7% in growth. In emerging countries the situation is worse: each percentage point above 64% will cost 2% in growth. But much depends on who is lending. Japan's total-debt-to-GDP ratio is in fact 228%, but most debt is held by Japanese citizens, and so not under risk of recall. {15}

Debt is historically written off by inflation, widespread bankruptcy or in debt redemption. America and the western nations have so far chosen to ignore these precedents, reducing their debt burden by debasing the currency (inflation) and printing money (quantitative easing). To maintain so inherently unstable a system they have also been obliged to create a currency hegemony, creating enemies abroad through wars and curtailing civil liberties at home. {16}

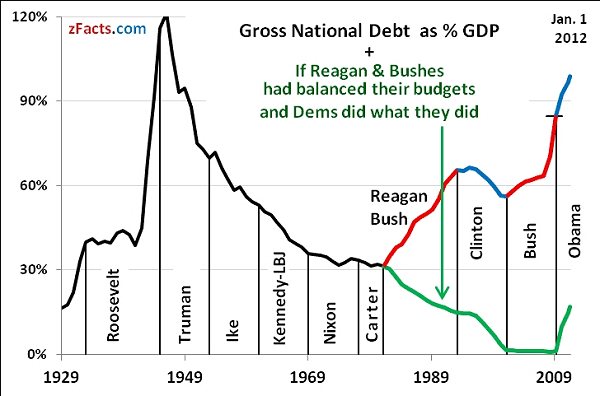

Growth of Debt

As of September 2014, the US national debt stood at $17.7 tn, to which should be added $7.8 tn for federal employee retirement benefits, accounts payable, and environmental/disposal liabilities, plus $23.8 tn in Social Security obligations and $27.3 tn for Medicare obligations. The national debt has grown steeply after major wars, been 'paid back' (generally inflated away) but increased in recent years by the 'war on terror', bailing out Wall Street and quantitative easing. {17}

The UK's national debt shows a similar pattern: an increase with wars, recessions and increasing trade deficits. Equally striking is household debt in western countries.

Suggested Solutions

Because the US national debt will soon be unsupportable — i.e. the interest payable becomes too socially destructive — methods of reducing the debt are constantly being discussed. Truth in Banking's solution is to greatly curtail the power of commercial banks by: {18}

1. Replacing them with state-owned banks offering high street banking facilities after the North Dakota model.

2. Paying state taxes through interest payable on loans: 2% for mortgages, 6% for credit cards, and 3-4% for commercial and vehicle loans.

3. Returning taxpayer surpluses, often amounting to trillions of dollars.

4. Educating the public in how money is created and controlled.

5. Nationalizing the Fed.

6. Abolishing the fractional reserve system.

These simple measures would end the increasing demand for resources and power inherent in our money policies, which are arguably the root causes of wars, social deprivation and environmental destruction.

Laurence J. Kotlikoff proposes switching from debt-based to equity banking. Banks would offer mutual funds comprising assets of various categories, duration and risk, an approach enjoying a large and contentious literature. The key problem, as always with utopian schemes, devolves on who supervises the guardians. Who will guarantee that the new, enlarged Federal Financial Authority will act in a fair, responsible and transparent manner? {19}

No doubt some more transparent scheme of checks and balances is not beyond the wit of man, but how could the national debt be paid off without collapsing the money supply, since every dollar 'in circulation' is matched by a dollar plus interest in debt? There are two ways:

The government could simply write off the debt by massive quantitative easing: the Fed would write a cheque to pay off the creditors of national debt, effectively abolishing itself. Creditors returned their money would need some other way of investing their funds, but the action need not be inflationary because no new money is created, particularly if done carefully, in stages to avoid panicking the markets. {20}

The second way is similar but uses the fiction of a 'high value platinum coin seignorage'. Essentially, the US Treasury mints a platinum coin, declares it worth $70 tn, deposits it with the Fed, and effectively writes off the national debt. Again the debt disappears, and with it the expensive interest costs imposed by the international banking houses.{21}

Modern Money Theory

Entirely a different approach is offered by Modern Money Theory. Good government aims at price stability and full (i.e. not less than 98%) employment, and so a more equitable society. The principle is simple, but counter-intuitive, or at least contrary to what banks, mainstream economists and politicians preach. We start with money, which in modern fiat currencies is simply a tax credit. A one dollar bill is an IOU issued by the Federal Government to the effect that the bill is good for the payment of one dollar of tax. No more than that. But note that money originates with the Federal Government. It is not made in the private sector but 'created out of nothing' by the US government, which is a sort of sovereign currency machine. That money 'pays' for Government spending on collective goods and services which the private sector supplies. The more money the Government spends, the more everyone benefits, the private sector accessing and leveraging that money through banks loans to create a healthy society with all the necessary goods and services. {22}

Certainly the government must control that money, to prevent too much money being issued for the same goods (inflation) or too little (deflation) but the constraints on an economy are labour, materials, energy and technical know-how. {22}

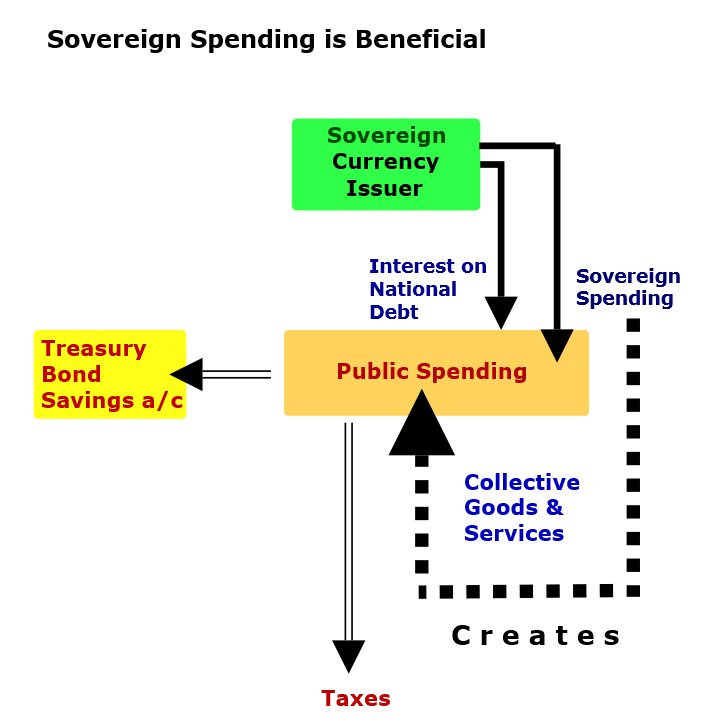

Today most transaction are not made with coins or bank notes but by digital transfer. One account is credited and another debited. Nor are taxes used to fund government spending. What would be the point of government collecting its own IOUs? Taxes are used to control the amount of money, and redistribute it between American citizens. Most payment is by digital transfer, and taxes simply drain the money out of the private sector, and cause it to disappear. In short, the Sovereign Currency Issuer creates collective goods and services by sovereign spending. It also pays interest on the National Debt, which is simply a measure of the total dollars that have been transferred from a checking account that pays no interest to a Treasury Bond account that does pay interest. That interest is not paid by present or future citizens from their hard-earned wages, therefore, but is again simply issued by the Federal Government. The trillions of Treasury Bonds owned by China are not then a threat to America's future: when repayment falls due, a digital entry will transfer them into China's checking account. {22}

In that light, many perceived wisdoms of the mainstream media become illusions. Governments do not resemble businesses or individuals that must balance their income and outgoings. Money is not what governments are indeed short of, but resources, employees and skills. Governments can always afford their spending programs. Government deficits mean increased wealth in the private sector, and 'balanced budgets' achieve nothing (budget surpluses being even worse, of course: they impoverish the private sector.) Social Security is not broken, nor is the trade deficit unsustainable. It's trust that manages banks and financial institutions — which makes it essential they act transparently and responsibly for the public good. {23}

An approach so threatening to the established order has not gone unchallenged. Thomas Palley argues that MMT would cause trade problems and serious financial instability in an open economy with flexible exchange rates. Robert P. Murphy called it 'dead wrong'. Monetarist governments in practice had great difficulty in measuring, let alone controlling the money supply. Logically, MMT may be irrefutable, but economics is not an abstract science independent of human needs, but an idealization of existing social behaviours — generally a rationalization or apologia for the world as it is. Economic downturns do indeed follow government surpluses, and policies that enabled all citizens to enjoy a more prosperous and productive life are surely to be welcomed. But money is far from being governed by the overreaching abstract laws of economics. Indeed, as the early Bank of England indicates (and Celtic coinages suggest), money may be created for one purpose but used for quite another. That the dollar bill is simply good for the payment of one dollar of tax may well be true, but that dollar has also come be used in many other ways that reflect our emotional and material needs, not least of them status, jobs, material satisfactions and purpose in life. MMT is likely to have little influence on mainstream thought, at least for the present, because its concepts do not engage with the values, traditions, customs and institutions that must change if a modern democracy would evolve in an orderly manner. (Nor did Monetarism have a detailed engagement with social realities either, of course: its heyday was brief and its achievements still contested.) {24}

Doomsday Scenarios

The likelihood of impending financial doom depends on our view of money, therefore, and the power of accounting sleights of hand to roll up debt. Another financial collapse would nonetheless place pressure on an American administration still persuaded that industry should serve finance rather than the other way round — even though many see finance as now destroying the American economy. {25}

Mainstream economists are divided in their view of debt, despite the sums involved. Whatever actions western governments now take, some form of bankruptcy seems increasingly likely, if only because debt is expanding rapidly, beyond the capacity of industry to absorb it by linear wealth creation. Currently, some 24 nations are technically bankrupt, and another 14 approaching bankruptcy. No major western nation can repay its debts, nor can Japan, or many of the emerging markets. China is in trouble, and the U.S. is the most indebted of all, having lived beyond its means for 50 years. Global sums are enormous: $200 trillion debt and $1.5 quadrillion in derivatives. Bail-ins that seize deposits to pay for hedge fund gambles will be unpopular, and ineffective: the sums are too large. Debt redemption of some type is therefore inevitable, though procedures are uncharted waters. The alternative is massively destabilizing trade reduction, and a fall in global stocks, bonds and property values of some 75-95%. {26}

Advocates of Modern Money Theory are much more sanguine. Debt is simply the money drained from the banking system to control inflation and employment. Repayment is a matter of digital entries, no more than that while the social and financial institutions remain sound: it's a non-issue if clear thinking and strong nerves prevail. {27}

References and Further Reading

Require the 128 references and 4 illustration sources? Please consider the inexpensive ebook.